Boom & Balance

The Charleston area growth predicted for 2030 is already here, and more is coming

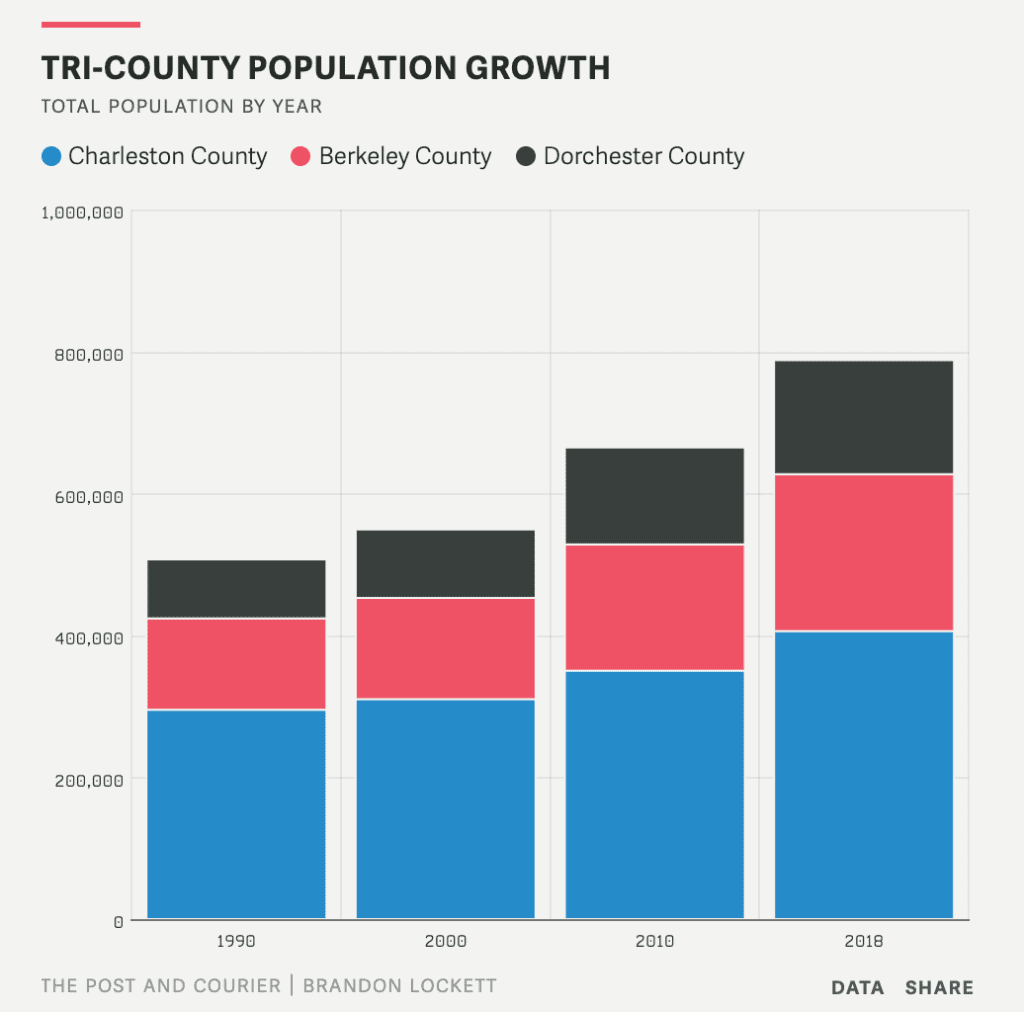

Lowcountry residents were shocked when a Clemson University study warned in 2003 that the Charleston area’s population could soar to nearly 800,000 by 2030.

“Honestly, I think people had trouble imagining that at the time,” said Jeffery Allen, one of the study’s authors.

“Everyone was hoping it wouldn’t grow like that, because that would be horrible.”

Horrible or not, the tri-county Charleston area’s population exceeded 800,000 in 2019 — 11 years earlier than the Clemson study predicted. Census estimates later this month will make that official.

“I think, unfortunately, it was one of those situations where people said, ‘We need to do something,’ but nobody really did,” said Allen.

There were plans — lots of plans — and one did prompt measures in Charleston County to address growth, although it too underestimated how much growth would come.

As development in the region accelerated in the 2000s, a consortium of local officials, business groups and planning officials spent several years forecasting what was to come and looking for ways to manage it. The resulting $1.5 million Our Region Our Plan study was published in 2012 and concluded the tri-county population could reach 873,479 by 2040.

“We weren’t factoring in Boeing, and we were in the midst of the recession,” said Kathryn Basha, planning director at the Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Council of Governments, which published the voluminous study.

The area’s population will certainly reach 873,479, but that milestone will be reached in the mid-2020s — about 15 years earlier than Our Region Our Plan predicted — unless the region’s growth abruptly slows remarkably.

“I think I said at the time that we may have understated what was going to happen,” said Larry Hargett, a Dorchester County councilman who chaired the Our Region Our Plan committee. “We’re trying to get ahead of it.”

South Carolina lost population to other states from the mid-1800s until 1970. Then, as if the tide turned and started coming back in, the population roughly doubled from 1970 to 2020 fueled by people pouring in from other states.

By 2040 the Charleston metro area will likely be home to about 1 million residents. All it would take to get there is building the more than 100,000 homes that have already been approved in development plans.

The rapid growth in Berkeley, Charleston and Dorchester counties has created jobs and economic opportunities, from the large Boeing and Volvo manufacturing plants to the retail stores and hospitals serving the growing population. That same growth has brought traffic problems, higher taxes, crowded schools, strained public services and complaints about diminished quality of life.

This year in the occasional series “Boom and Balance,” The Post and Courier will explore the challenges ahead and the solutions being tested as rapid growth and development continue to outpace expectations and reshape the Charleston metro area.

Billions to ease traffic

When Charleston area residents air complaints about development, the top response is often traffic. It’s become an issue in local political campaigns and has prompted higher taxes and billions of dollars in planned road construction.

“I used to go to the Flowertown Festival (in Summerville),” said Al Miller, a West Ashley resident who moved to Charleston in the 1970s. “I don’t even try to get there now.”

“Summerville has exploded, and the little town of Goose Creek, I was amazed at how it’s grown,” he said. “If Charleston was like it is now, then, I probably would not have come here.”

Building new roads and new bridges, and widening existing roads, is a seemingly never-ending task with an ever-rising price tag. The area’s largest project, the state-run Lowcountry Corridor plan to widen Interstate 526 from West Ashley to Mount Pleasant from four lanes to eight, is expected to cost more than $2 billion.

“If we could wave a magic wand and make it six lanes today, it would barely operate at a passing grade, maybe for a year or two,” S.C. Department of Transportation Project Director Joy Riley said in February.

One problem has been that when roads are built or widened to ease traffic or create new hurricane evacuation routes they tend to pave the way for more development. Interstate 526 made it possible to develop Daniel Island and the Cainhoy peninsula — where a development of over 9,000 homes is under construction — and the Glenn McConnell Parkway prompted more growth in West Ashley.

State and local governments have struggled to keep up

Jason Crowley of the Coastal Conservation League said the Our Region Our Plan study did prompt some important changes. Charleston County approved — and defended in court — regulations to limit development in rural areas, and the state passed a law requiring towns and cities to each develop a long-range vision for development known as a Comprehensive Plan.

“It has put a check and balance on how we grow as a region,” Crowley said.

Despite small victories in planning, the tri-county area gained more than 238,000 residents since 2000, and all the vehicle traffic that came with them.

To fund road work, South Carolina motorists are paying higher gas taxes and Charleston area residents are paying extra sales taxes, funding hundreds of millions of dollars in road projects in three counties. Mount Pleasant, where the population tripled since 1990, has imposed steep impact fees on development that add costs to the construction of new homes and businesses.

Hargett said Dorchester County also plans to be “loading up on impact fees” so that the costs of growth and development fall less heavily on current residents.

“Some developers and builders won’t like it, but sewer, water and road construction — they are going to have to pay for that,” he said.

Waiting in vain for a train

The need for traffic relief is clear to anyone who commutes on I-26 and I-526, but traffic can be appalling in places where massive subdivisions have been built along two-lane roads, such as S.C. Highway 41 in Mount Pleasant and S.C. Highway 176 near Cane Bay High School in Berkeley County.

Longtime residents find the conditions oppressive, but some newer residents don’t share that opinion.

“I’m from New York City, I lived in (New) Jersey; bottom line is the growth is not that bad,” said Jack Adzema, who retired to Del Webb at Cane Bay nearly five years ago. “We go to the beach all the time.”

There have been growing calls for efficient mass transit in the region where rivers, marshes and existing development makes new ways to get around hard to develop. The historically underfunded bus system, CARTA, has been providing more options, including express buses and no-fare routes on the Charleston peninsula, but the trains and trolleys that once served the area may be gone for good.

“The way the buses are, if my wife’s daughters who are at College of Charleston use them, it takes an hour and a half,” said Ralph Papa, of West Ashley. “So every day we drive down to the College of Charleston.”

“If they would only have a trolley or light rail from West Ashley, that would be awesome,” said Papa, who moved from Philadelphia, which has an extensive train and trolley network. “Look at (Highway) 17 and how insane that traffic is, and it’s only going to get worse.”

The area’s Council of Governments spent years and millions of dollars studying the potential for passenger rail service. Those studies concluded the best option was the planned Lowcountry Rapid Transit bus system from Summerville through North Charleston to Charleston, which will cost an estimated $360 million. A passenger rail line serving the same areas would have cost an estimated $2 billion.

“We still don’t have what it would take to support commuter rail,” Basha, the COG planning director, said. What it would take, she said, is more population and higher density.

The Coastal Conservation League has long argued for more dollars to go toward transit solutions rather than road-widening projects, but for the near future that means buses.

“We were never going to have a train,” said Crowley.

He said local governments could do more to help with traffic by requiring developments to be connected to each other and to a network of local roads. For example, Charleston’s Johns Island community plan recommended creating a grid of streets on either side of Maybank Highway, but that has not been done.

Crowley said the huge Nexton and Carnes Crossroads developments are a missed opportunity because they share a border but are not connected with roads. As a result, a Carnes Crossroads resident who wants to dine at a restaurant in the Nexton development must join all the traffic on U.S. Highway 17A to get there.

“It is not too late,” Crowley said, blaming the lack of a road connection on poor intergovernmental planning.

Many governments are involved in the region’s development, and they don’t always have the same vision. Different parts of the Nexton development are in Berkeley County and the town of Summerville, for example, while Carnes Crossroads next door is in Goose Creek.

One region, 30 governments

Development has impacts that don’t respect municipal boundaries — traffic, flooding and school crowding, to name a few — but the three counties and 27 towns and cities that make up the Charleston metro area have different goals and regulations.

Consider Mount Pleasant, which in recent years has tried to curtail development with moratoriums on apartment construction, annual limits on building permits and sky-high development impact fees. While those measures could slow development inside the town limits, parts of the East Cooper area are governed by Charleston County, and just across the Wando River a 9,000-home development is underway on the Cainhoy peninsula; it’s permitted by the city of Charleston.

Likewise, Charleston years ago created an “urban growth boundary” to mark the end of the suburbs in West Ashley, but developments have leapfrogged the city limits and that boundary line. North Charleston extended its boundaries across the Ashley River and encouraged development along S.C. Highway 61, behind Charleston’s growth boundary, permitting at least 1,000 homes on the Watson Hill tract.

In western Charleston and Dorchester counties, east of the Edisto River, the Summers Corner and Spring Grove developments could have 6,000 and 4,500 homes, respectively, and a 700-acre industrial park is also planned at Spring Grove.

The Spring Grove development abuts the small town of Ravenel, home to about 2,700 people, which has no jurisdiction over the plan but is preparing for the growth to come.

Ravenel has had a development moratorium in place since November 2018 to prevent substantial development until the town can complete its Comprehensive Plan and update its zoning rules.

“I would say there is definite concern about the growth that is coming,” said Planning and Zoning Administrator Mike Hemmer. “We need to be prepared for it to happen, and not just have growth for growth’s sake.”

Some of the largest developments in the region are taking places on edges of the Charleston metropolitan area where substantial tracts of timber and hunting land have allowed for nearly a dozen plans that each call for thousands of homes. Spring Grove and Summers Corner are part of the 72,000-acre East Edisto timber properties previously owned by paper company WestRock and its corporate predecessor MeadWestvaco.

Although many thousands of homes and an industrial park are planned, 53,000 acres of the property were protected by the East Edisto plan, which was hailed as a landmark agreement by conservationists and an example of managing growth.

Charleston County has also protected more than 21,000 acres of land from development through its Greenbelt program, which uses public funds to buy land or development rights.

“One way Berkeley County could take steps toward creating a hard urban growth boundary, like Charleston has, is to create a greenbelt program,” said Crowley.

Regional planning studies have called for governments to cooperate and use smart-growth planning tools to guide development — concentrating housing near mass transit, for example, and blending commercial and residential development in order to reduce commutes and shopping trips.

“Not only does urban sprawl rapidly consume precious rural land resources at the urban fringe but it also results in landscape alteration, environmental pollution, traffic congestion, infrastructure pressure, rising taxes and neighborhood conflicts,” said the Clemson study, in 2003.

The Charleston metro area has one of the nation’s lowest unemployment rates and continues to win top rankings on national lists of places to visit, work and vacation. People move to the area for many reasons, but that popularity comes at a cost.

Nearly a decade after the Clemson study Our Region Our Plan warned that sprawl was continuing, the pace advanced unabated. The ripple meant “not only to the loss of farmland and open space,” it said, “but also increased the stress on our natural environment, contributed to congestion and limited our transportation choices.”

Despite all the growth and development, there’s room for plenty more, particularly in Berkeley and Dorchester counties. Both counties have already seen more rapid population increases since 1990 than Charleston County, and Dorchester’s population has nearly doubled.

“We have lots of land, and relatively speaking, it’s cheap land,” said Hargett. “We have a lot of places left to build; Dorchester County is 45 miles long.”

“Some people have said, ‘Why don’t you put up a sign on I-95 saying that we’re full?’ But that’s not going to happen,” Hargett added.

What’s more likely to happen is that Berkeley, Charleston and Dorchester counties will continue to grow, from more than 800,000 residents now to more than 1 million before 2040. How that growth is managed will be up to the leaders of 30 local governments, and the citizens who elect them.